Albany Agrees to Resurrect the 421-a Tax Exemption

Taxpayers and Tenants Should be Disgusted

Albany has come to an agreement on that includes resurrecting the 421-a real estate tax exemption, with a vote on the full State budget expected today. There is no acceptable reason that everyone except luxury real estate developers should be expected to pay their taxes. Taxpayers and tenants should be disgusted.

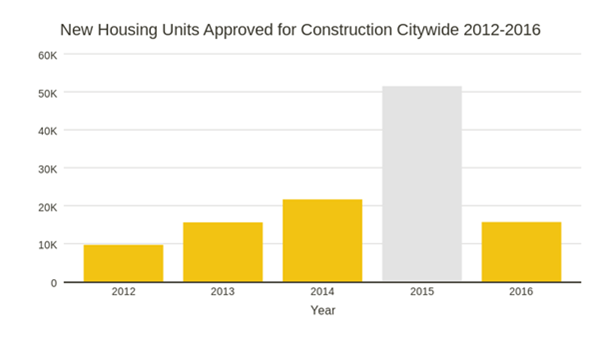

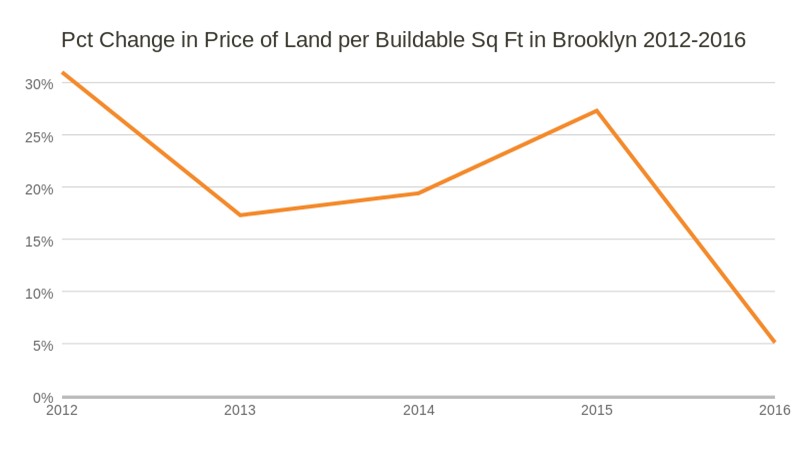

We will need the $1.4 billion – and growing – that we spend each and every year on 421-a to fill the holes that will be left in the local budget by Trump’s federal budget cuts for essential services. 421-a does little to actually create affordable housing, with 79 cents of every 421-a dollar spent going to luxury development, and only 11 cents going to support affordability. A growing body of evidence suggests that the 421-a exemption doesn’t even accomplish the most minimal public purpose of incentivizing new market-rate development.

Resurrecting 421-a is also a body blow to tenants because changes in the law, for the first time, include the interests of the construction trade unions, which severely limit the ability of tenant-friendly legislators to use the program as leverage to defend or strengthen rent regulation against and anti-tenant legislators. Rent regulation is New York City’s most effective affordable housing and community-stability preservation program, which is now left far more vulnerable. This is especially true because under the new agreement, 421-a expires in 2022 and rent regulation expires in 2019, stripping tenants of essential leverage.

What is the New 421-a Program?

The new 421-a program, now titled “The Affordable New York Housing Program,” is essentially an expanded and amended version of the expired June 2015 421-a exemption that passed the legislature, but with modifications intended to resolve the conflict created from a trade union wage provision that was inserted at the last minute. This subsequently led to legal complications and suspension of the exemption.

The new 421-a program does not improve the affordable housing requirements passed by the legislature in June 2015, but it does add significant cost to the taxpayer.

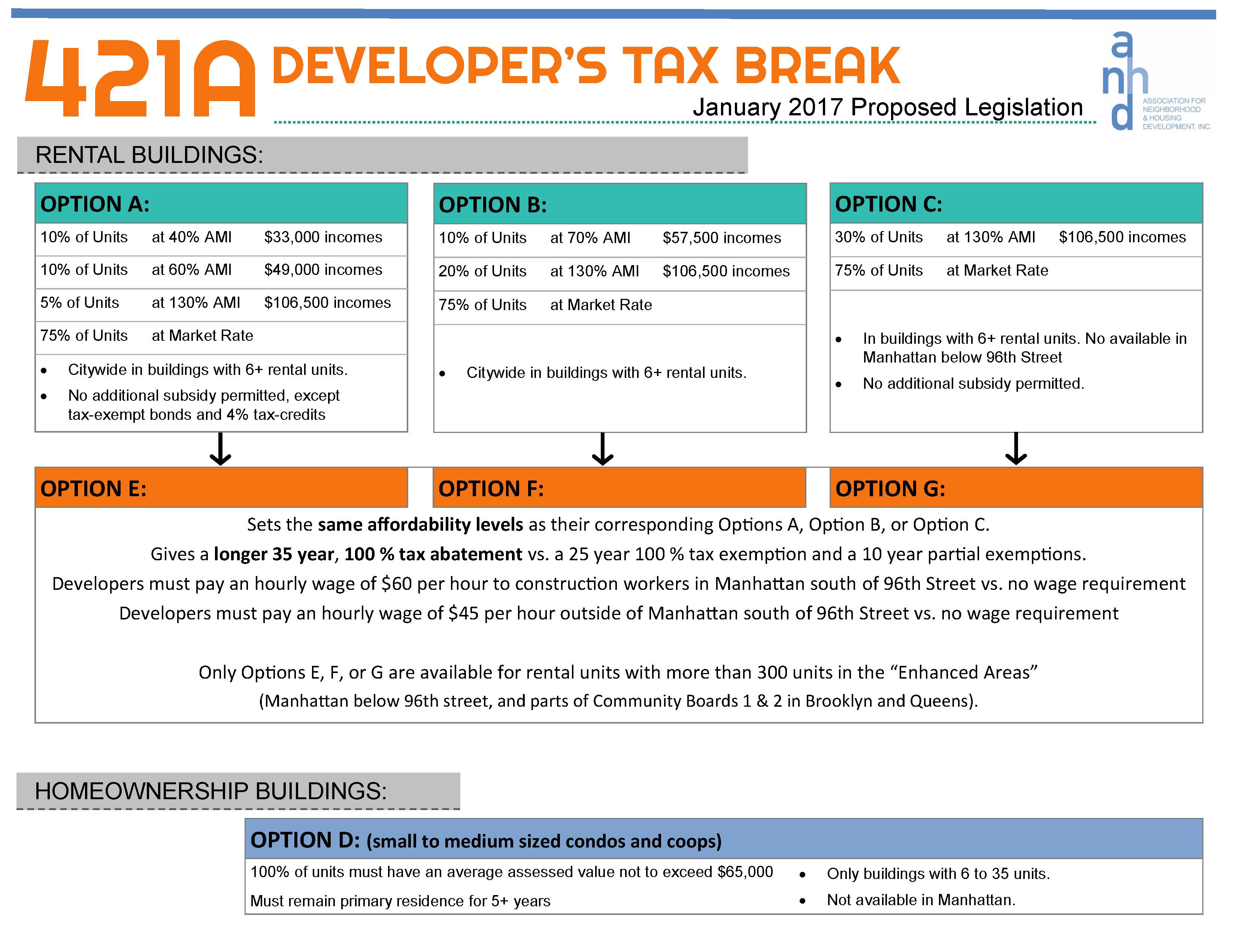

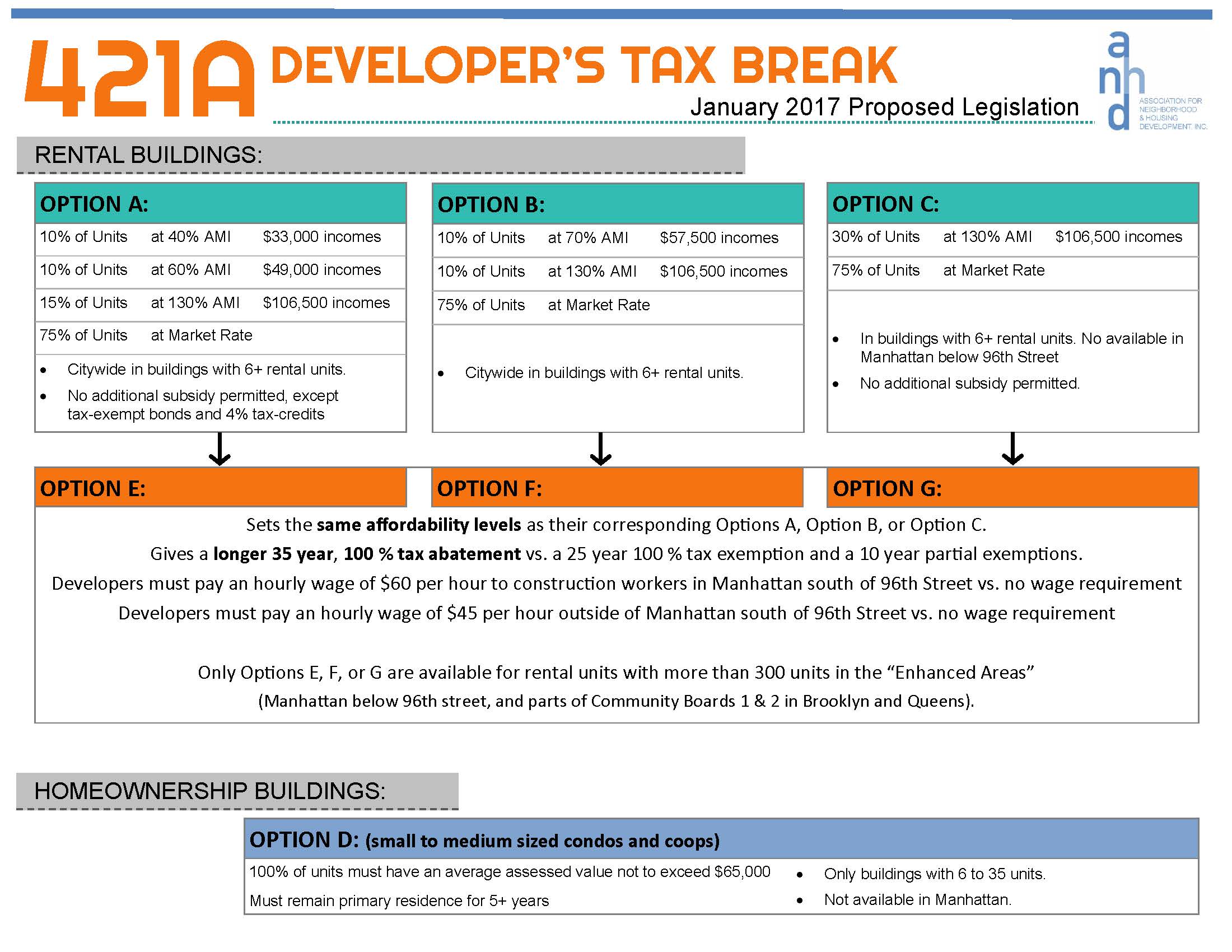

The June 2015 version was citywide and would have been used by almost all new residential development projects over 6 units, allowing developers affordability Options A, B, C, and D. (See image below for an explanation of the options) The new program adds Options E, F, and G and requires developers to pay higher construction wage levels. The new Options E, F, and G also extend the length of the tax exemption to an unprecedented 35-year, 100% exemption. This is a major increase in the lifetime value of the exemption to the developer and a major increase in the cost to the New York City taxpayer.

The program currently costs taxpayers $1.4 billion a year – and growing – and the NYC Independent Budget Office have estimated that the changes to the new program will add significant additional cost.

The proposed new REBNY program is citywide, and would widely be used across most neighborhoods. Development of new buildings with 300+ rental units will be required to participate in the program in some areas and eligible to participate in all other areas of the City. The new program is exceptionally generous to the developer, and most will take advantage of this financially generous opportunity.

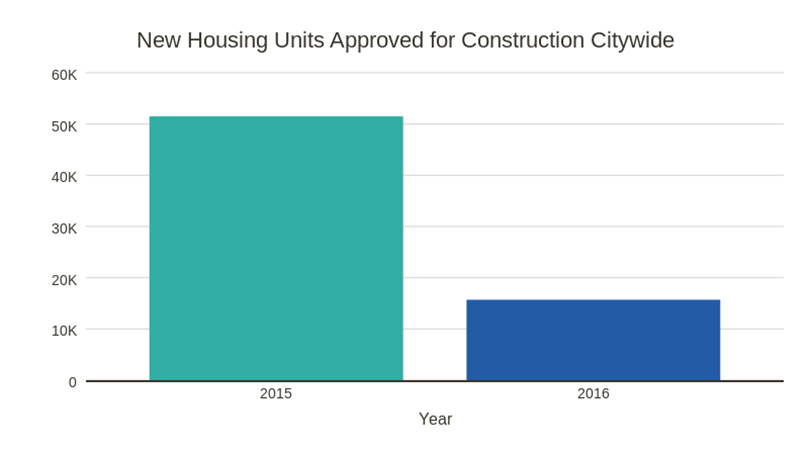

And the increase in cost won’t just come after year two of the extended tax exemption; it will come immediately. Developers will find the enhanced benefit irresistible since it allows them to not pay taxes for an additional ten years. We will see a rush of developers applying for the new 421-a program and see developments from the last 1.5 years retroactively being granted 421-a, at a great cost to taxpayers.

No additional affordable units, or deeper level of affordability will be generated by the REBNY proposal, and the increase in the length of affordability is minor. The primary beneficiaries will be market-rate and luxury real estate developers, who will have their already substantial public subsidy increased by an estimated 22.5% in each new building. A fraction of the increased value given to the developer will be passed along in the form of higher wages for the short-term construction labor.

How Do the New “Options” Work?

- Option E is allowed within any of the Enhanced Affordability Areas, and requires 10% of the apartments be affordable at 40% of Area Median Income (AMI), 10% at 60% of AMI, and 5% at 120% AMI. The average hourly construction wage must be $60. Additional public subsidy is not allowed.

- Option F is allowed within any of the Enhanced Affordability Areas, and requires 10% of the apartments be available at 60% of AMI, and 20% at 130% AMI. The average hourly construction wage must be $60 an hour. Additional public subsidy is allowed.

- Option G is allowed only within the Brooklyn and Queens Enhanced Affordability Areas, and requires that 30% of the new housing is affordable at 130% of AMI. The average hourly construction wage must be $45 an hour. Additional public subsidy is not allowed.

- Any building with 300+ rental units outside of the Enhanced Affordability Areas can opt-into Option G, which, given the extraordinary value of the 35-year 100% abatement to the developer, is the most likely outcome.

ANHD 2016 Building the Community Development Movement

ANHD 2016 Building the Community Development Movement